COLLABORATION, IMMIGRATION AND TRACES OF A LIFE

A chance collaboration ignited when Mexico City artist Marisa Boullosa knocked at my door this summer, armed with two large plasticized exhibition banners. She had moved away from San Miguel about the time I was moving out of MARIPOSAS, a women's project I engaged in between 2009 and 2012. After first positing the idea that the seamstresses create bags out of the banners, she graciously granted me permission to recycle them as I see fit. My first inclination, not surprisingly, was to create a huipil from them.

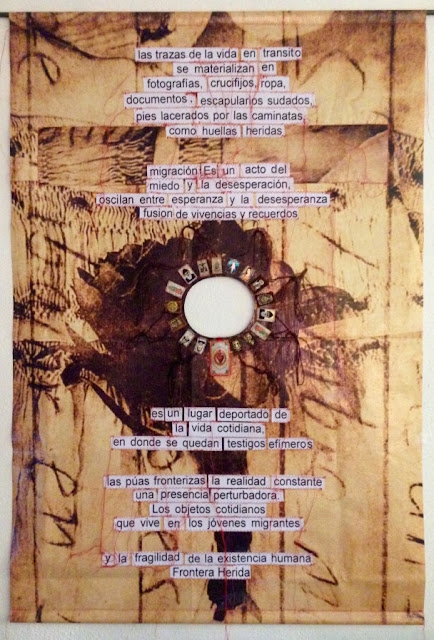

Let me say that I'm a longtime fan of Marisa's work, as she tackles issues of migration, border issues, women's rights and human rights, imbuing them with truth, beauty, justice and compassion. This led to my second inclination: to collaborate with her on this material she had gifted me with. One banner was a detail of her work as seen in her 2014 exhibition, Frontera en Memoria, at the Cervantino Festival in Guanajuato. The other was a smaller image alongside a lengthy exhibition statement by Blanca Gonzáles Rosas.

Having met and spoken with so many Central American migrants working their way north, I had already been contemplating a huipil to speak about their journey. Many of these young people jump off the train, La Bestia, as it passes through San Miguel. Here they find a tourist town full of compassionate and helpful people, but also corrupt police who take their meager possessions, threatening to turn them in to immigration officials. Their tales of danger and desperation, losing along the way all traces of their lives, melt my heart and sometimes threaten to dissolve my belief in humankind.

Marisa's regalo that day provided the impetus and the materials I would need to artistically speak about this crisis. After many emails back and forth, what emerged is an open huipil with poem in Spanish, created from the exhibition statement, as one would do with refrigerator poetry magnets.

Visually assembling words and phrases before cutting them out, then checking translations, grammar and punctuation online with Marisa led me to the question of how to apply them to the huipil. In her own work, red thread in a zig-zag stitch is both a symbolic gesture and a prominent feature that I chose to incorporate here.

Then I needed something for the center, where a traditional huipil would be folded and fitted over the head of the wearer like these traditional huipils:

Taking a word from the statement-turned-poem, I went shopping for scapulars, escapularios, at the religious items stand in front of the Oratorio church.

For Catholic migrants, this important talisman holds the promise that the wearer will escape the flames of hell if he or she dies with it on. It's part of nearly every traveler's necessities, whether crossing las fronteras or walking the Camino de Santiago in Spain. I chose to use a variety, creating the collar of the huipil.

Let me say that I'm a longtime fan of Marisa's work, as she tackles issues of migration, border issues, women's rights and human rights, imbuing them with truth, beauty, justice and compassion. This led to my second inclination: to collaborate with her on this material she had gifted me with. One banner was a detail of her work as seen in her 2014 exhibition, Frontera en Memoria, at the Cervantino Festival in Guanajuato. The other was a smaller image alongside a lengthy exhibition statement by Blanca Gonzáles Rosas.

Having met and spoken with so many Central American migrants working their way north, I had already been contemplating a huipil to speak about their journey. Many of these young people jump off the train, La Bestia, as it passes through San Miguel. Here they find a tourist town full of compassionate and helpful people, but also corrupt police who take their meager possessions, threatening to turn them in to immigration officials. Their tales of danger and desperation, losing along the way all traces of their lives, melt my heart and sometimes threaten to dissolve my belief in humankind.

Marisa's regalo that day provided the impetus and the materials I would need to artistically speak about this crisis. After many emails back and forth, what emerged is an open huipil with poem in Spanish, created from the exhibition statement, as one would do with refrigerator poetry magnets.

|

| LAS TRAZAS, huipil by Lena Bartula, 2015 |

Visually assembling words and phrases before cutting them out, then checking translations, grammar and punctuation online with Marisa led me to the question of how to apply them to the huipil. In her own work, red thread in a zig-zag stitch is both a symbolic gesture and a prominent feature that I chose to incorporate here.

Then I needed something for the center, where a traditional huipil would be folded and fitted over the head of the wearer like these traditional huipils:

Taking a word from the statement-turned-poem, I went shopping for scapulars, escapularios, at the religious items stand in front of the Oratorio church.

For Catholic migrants, this important talisman holds the promise that the wearer will escape the flames of hell if he or she dies with it on. It's part of nearly every traveler's necessities, whether crossing las fronteras or walking the Camino de Santiago in Spain. I chose to use a variety, creating the collar of the huipil.

|

| Neckline of scapulars in Lena Bartula's huipil LAS TRAZAS |

"Traces of a life in transit

materialize in photographs, crucifixes, clothing,

documents, sweaty scapulars,

feet lacerated by the roads,

like wounded footprints..."

"....it is a place deported from

everyday life, where ephemeral witnesses remain.

Barbed borders the constant reality

a disturbing presence."

- excerpts from "La Traza" by Lena Bartula, written in Spanish from statement for "La Frontera en Memoriam," an exhibition by Marisa Boullosa.

Comments